Among the major opening lines in chess, few are as daring, or downright outrageous, as the Muzio Gambit and especially the Double Muzio Gambit. After just eight moves, White willingly gives up two pieces. That’s right: down two pieces in under 10 moves. According to chess author Johann Lowenthal, the idea came from the great Paul Morphy, though he reportedly only used it in a game where he spotted his opponent a knight from the start.

- e4 e5

- f4 exf4

- Nf3 g5

Black opts for the Classical Defense to the King’s Knight’s Gambit, an age-old response that remains one of the most ambitious, aiming to solidify the pawn on f4 with support from …h6 and …Bg7.

- Bc4!?

White tempts Black into triggering the famous knight sacrifice. For players preferring a less volatile line, there’s 4. h4 followed by 5. Ne5, steering into the Kieseritzky Gambit, more measured but less explosive.

4… g4!?

Frankly, it would be fun if this move were required by the rules in such positions. Of course, 4…Bg7 is safer, but that doesn’t really suit the spirit of a gambit event, does it?

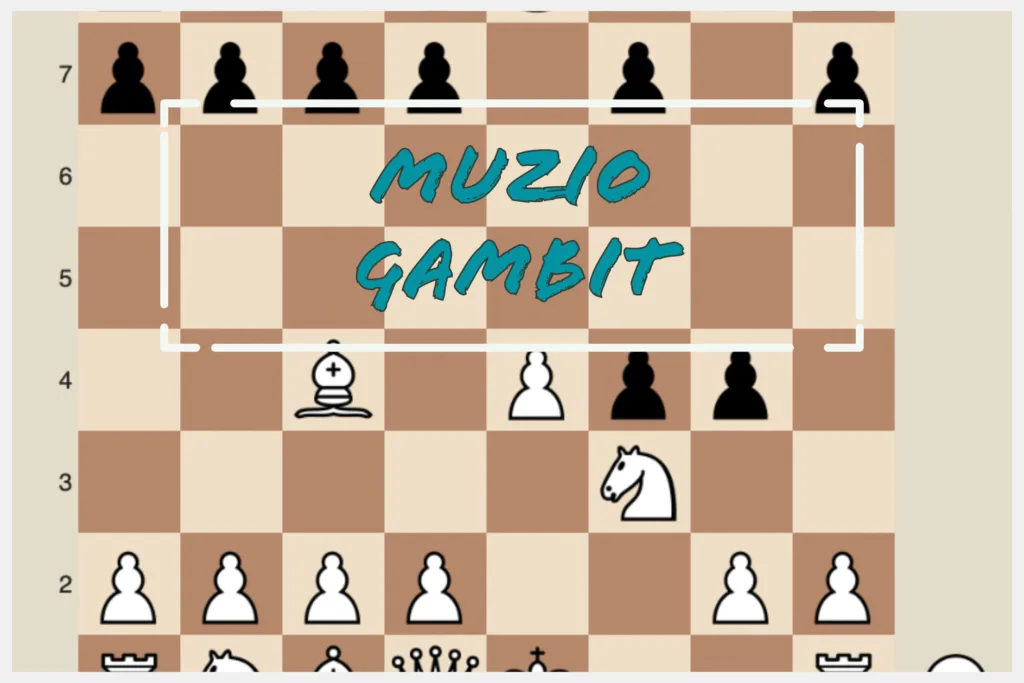

- 0–0!

And here it is, the classic Muzio Gambit.

Muzio Gambit

A Product of the Romantic Era

The Muzio Gambit is a child of the Romantic chess era, a time when brilliance was measured by how many pieces you could sacrifice en route to checkmate. Between the late 1700s and 1880s, players like Anderssen, Morphy, and La Bourdonnais sought the sublime through tactical storms and flamboyant finishes. This was the era where the King’s Gambit ruled supreme, and the Muzio, an explosive subvariation, fit the mood perfectly.

Its origins date back even further. The earliest analysis is credited to Giulio Cesare Polerio in the 16th century, but the name “Muzio” was a happy accident: chess author Jacob Sarratt mistakenly attributed it to “Mutio d’Allesandro” in the 1800s. No matter the name, the spirit of the opening hasn’t changed in centuries: sacrifice early, attack relentlessly, and let the chips fall where they may.

Why Play the Muzio?

The Muzio isn’t subtle. It’s not for the faint-hearted. But it is a fantastic tool for learning the art of attack. Why?

- It teaches initiative. White must keep the tempo, or risk being left material-deficient with no compensation.

- It rewards creativity. With so many open lines and attacking possibilities, each game becomes a new canvas.

- It’s surprisingly practical. Against an unprepared opponent, especially in blitz, the Muzio can be deadly.

In fact, Soren Jensen used it to beat Frode Olav Olsen Urkedal, rated 564 Elo points higher, at the 2013 Reykjavik Open. And even grandmasters like Hikaru Nakamura have used it in high-level blitz events, famously defeating Dmitry Andreikin with a breathtaking attack in 2010.

White goes all in with this castling move. There are other ways to toss the knight, like the Lolli Gambit (5. Bxf7+), the Ghulam Kassim Gambit (5. d4), and the McDonnell Gambit (5. Nc3). Of those, only the last offers decent chances, as the Salvio Gambit (5. Ne5?) backfires horribly.

When Black Declines

What if Black sidesteps the madness?

5…d5!

This is the Muzio Declined, a line that tries to challenge White’s center before grabbing the knight. Now White can respond:

6.exd5 gxf3

7.Qxf3 Bd6

Or avoid early exchanges:

6.Bxd5 gxf3

7.Qxf3 c6

Even here, White enjoys rapid development and long-term pressure. Yes, Black is up a piece. But the open lines, weak light squares, and lagging development give White excellent chances.

5… gxf3

Black accepts the second piece. Trying something like 5…d5?! doesn’t help much, it only slows down the attack by a pawn. In Aurbach – Spielmann, Abbazia 1912, play went:

- Qxf3 Qf6

This is the standard follow-up, although 6…Qe7 deserves some attention too. For instance, in Steinitz – Anderssen, London 1862, play continued:

This is generally seen as favorable for White, though ECO’s second edition suggests 12…Bb7 for an unclear fight, planning to castle queenside. And there are other playable directions for White here too, moves like 7. b3, 7. d3, or even 7. Qxf4!? can work. That last one, 7. Qxf4, invites the line:

And now it’s White pushing for initiative.

- e5

Yes, moves like 7. d3 or 7. c3 are more cautious, and perfectly viable. But if you’re playing the Double Muzio, you’re not here to tiptoe. This pawn thrust is bold, risky, and incredibly exciting. After 7…Qxe5,

8. Bxf7+ !!?

And we’re off! This daring bishop sacrifice marks the dramatic entry into the Double Muzio Gambit.

Double Muzio Gambit

Despite its stylish pedigree and flair, the Double Muzio Gambit has received little love from the theory books. In fact, most of the published analysis is flat-out wrong. That’s not all that shocking. Grandmasters can’t risk playing something this wild without deep preparation, and few are willing to spend hours crunching lines that opponents can sidestep with ease. As a result, the gambit’s secrets remain mostly buried, waiting to be unearthed by those eccentric, fearless tacticians who pop up now and then at obscure gambit events.

As for this gambit’s potential? Let’s just say David Bronstein thought it was something special. In 200 Open Games (page 8), he singled it out with high praise, saying that this gambit alone “would be sufficient to earn for the [King’s Gambit] the eternal gratitude of chess-players.” Hopefully, once you’ve seen what unfolds in the game below, you’ll agree. The lines are chaotic, beautiful, and not for the faint of heart.

8…Kxf7

Though playable, 8…Kd8 hardly serves as a proper rebuttal. White’s most effective follow-up likely involves 9 d4 Qxd4+ 10 Kh1, then Bd2 and Bc3, just as Marshall played versus Moreau at Monte Carlo in 1903 (1–0 in 29 moves).

9. d4 Qxd4+

An alternative here is 9…Qf5, an option recommended by Steinitz. The common response goes 10 g4 Qg6 11 Bxf4 Nf6 12 Be5 Be7 13 Bxf6 Bxf6 14 Nc3. Yet, despite books often claiming White holds the upper hand, they’re overestimating, Black can simply play 14…Kg7!, maintaining most of the material advantage.

10. Be3 Qf6

Choosing 10…Qg7 instead would at least force a draw after:

But White can push harder too, seeking victory. For instance, 19 Qd3+ Kf7 20 Nh5+!?, or even earlier with 16 Nxc7?! or 16 Qc4!?

11. Bxf4!

Morphy’s old path 11 Qh5+ Qg6 12 Rxf4+ Nf6 13 Rxf6+ Kxf6 14 Bd4+ doesn’t quite cut it if White still has a queen’s knight to bring out. After 14…Kf7 15 Qd5+ Qe6 16 Qf3+ Ke8, Black has a firm material advantage, for example, 17 Bxh8?? Qe1+ mates in four.

Keres proposed 11 Nc3!? instead, aiming to punish 11…fxe3?! with 12 Qh5+, launching a ferocious attack. One solid counter is 11…Ne7 12 Nd5 Qf5! 13 Nxc7 Ng6! 14 Nxa8 Na6, where White restores material balance, but his stranded knight on a8 may become a long-term liability.

That said, 11 Bxf4! ushers in the core Double Muzio position, a battleground I’ve revisited and reanalyzed for over thirteen years. My view? Objectively, it’s equal.

11…Ne7

This is the book move, though not necessarily the best. Let’s look at some notable alternatives:

(a) 11…Bc5+? allows White to paint a tactical masterpiece:

(b) 11…Bg7? has appeared frequently, based on this game:

(c) The move 11…d5 may not be found in standard theory, but it proves significantly more resilient than many conventional continuations. After 12 Nc3 Ne7 (note that 12…c6? falters quickly due to 13 Qh5+ Qg6 14 Bd6+ Nf6 15 Rxf6+ Kxf6 16 Qe5+ Kf7 17 Rf1+, or 14…Ke8 15 Rxf8+ Kd7 16 Qe5! Qe6 17 Bxb8!), play continues 13 Nxd5 Nxd5 14 Qxd5+ Be6 15 Qxb7 Bc5+ 16 Kh1 Nd7 17 Bg5! Qxf1+ 18 Rxf1+ Kg7! (instead, 18…Kg6 19 Qe4+ Kxg5 20 h4+! Kh5 21 Qxe6 Raf8 22 Rxf8 Rxf8 23 Qxd7 Kxh4 24 Qh3+ Kg5 25 Qg3+ followed by 26 Qxc7 would be disastrous). Now 19 Bf6+!! Nxf6 20 Qxc7+ Kg6 (20…Nd7? 21 Qg3+ Kh6 22 Rf4 Be7 23 Qe3! leaves White clearly better; while 20…Bf7!? 21 Qxc5 Rhf8 22 Qe7 Nd5! remains complex) 21 Qxc5 threatens various continuations like 22 Qe2, 22 Qe7, or 22 h4 followed by 23 Qg5+. For instance, 21…Rhf8 22 h4! h6?! (22…Ne4! 23 Rxf8!±) 23 h5+! Kf7 (23…Kg7 24 Qe7+) 24 Qe5 Ke7 25 Re1+-, giving White a decisive edge.

Or it could go like this game:

(d) A personal favorite defensive try is the lesser-known 11…Nc6!?, aiming for …Bc5+ and …d6, thereby sidestepping earlier disasters. In Rawlings – Millican, correspondence 1987, the line progressed with 12 Nc3 Bc5+ 13 Kh1 d6 14 Qh5+ Qg6 15 Be5+ Bf5!? 16 Rxf5+ Ke6 17 Bxh8 Qxf5 18 Re1+ Ne5 19 Qe2! Nf6 20 Bxf6 Qxf6 21 Ne4 Qf4 22 g3 Qf5 23 Rf1 Qg4 24 Rf6+ Ke7 0–1. A better path for White is 14 Ne4, almost compelling 14…Qf5.

There’s a lichess account named don_vito_76 who won a couple of games in this line by checkmating in 15 moves, like this:

FAQs: Muzio Gambit at a Glance

Is the Muzio Gambit good?

Yes, for tactical players and romantic souls. It’s playable and practical, especially in fast games.

How should Black respond?

Accept with 5…gxf3 and defend the f4 pawn with 6…Qf6. Then develop quickly and carefully.

How should White play?

Stay aggressive. Consider 7.e5, prepare d3, and don’t fear entering the Double Muzio if you’ve calculated it.

Is it played at the highest level?

Rarely in classical, but it has been seen in elite blitz games and online bullet.

I’m Xuan Binh, the founder of Attacking Chess, and the Deputy Head of Communications at the Vietnam Chess Federation (VCF). My chess.com and lichess rating is above 2300. Send me a challenge or message via Lichess. Follow me on Twitter (X) or Facebook.

1 thought on “Muzio Gambit: The Most Dangerous Gambit in Chess (Full Guide)”

Comments are closed.