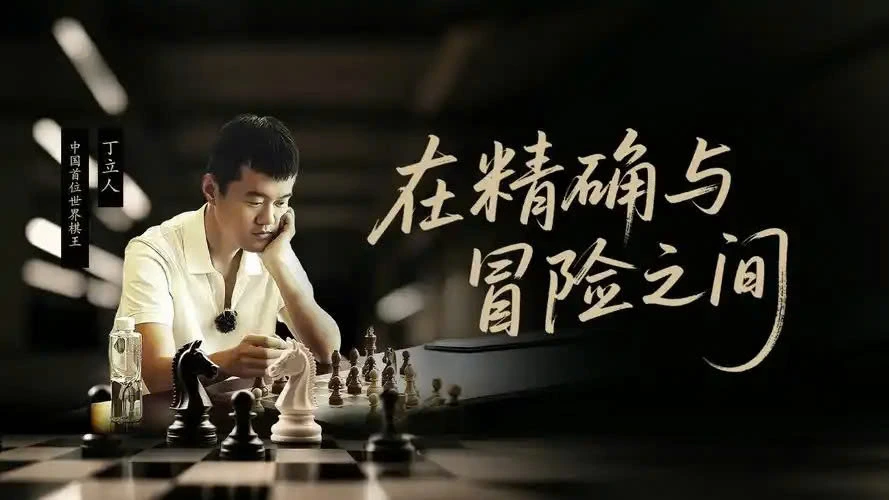

In April 2023, the chess world watched in silence as Ding Liren, a quiet law graduate from Peking University with a meticulous playing style and a deep fear of losing, became China’s first World Chess Champion. But while the world celebrated a milestone, Ding Liren sat in a quiet room, his face buried in his hands. Later, he admitted he cried after the final game. The moment didn’t look like triumph, as it looked like relief, even grief.

Two years later, Ding remains an enigma: a man who thinks like a machine, feels like a poet, and plays like a philosopher trying to translate truth into 64 squares. He has been in a long stalemate, not on the board, but within himself.

A Law Student’s Escape

At Peking University, Ding floated through law classes with low grades. Mock trials and debates didn’t interest him. “Legal facts require evidence,” he explained, “but not all facts can be traced.” Chess, on the other hand, offered clarity. “All its changes can be seen clearly on the board,” he said in an interview with Chinese media The Paper. “Or at least calculated by a computer.”

This quote reveals his worldview: precision is beauty, and ambiguity is unwelcome. In Ding’s universe, chess is not a war game or a spectacle. Somehow it’s a structured search for perfection. He once said he liked to “play chess that conforms to the principles of chess.” That may sound dry, but for Ding, this is romance: profound moves, no waste, as beautiful as a mathematical proof.

The Engine Generation

Ding is part of the generation shaped, some might say consumed by chess engines. While the greats before him were human calculators, Ding watches machines play against machines just for pleasure. “I’ve long been thinking about how to play more like an engine,” he told a reporter. “I don’t think about beating it. It’s impossible.”

For Ding, the engine isn’t a threat. It’s an oracle. He once became excited while explaining how the h-pawn – long considered cannon fodder – was reimagined by engines as a powerful attacking tool. He was almost in awe. “You can’t even see the point of a move until ten moves later.”

This fascination with engines sharply contrasts with 2024 World Champion Dommaraju Gukesh, who famously didn’t use an engine until he was 16. Gukesh chose intuition over computation in his formative years, while Ding willingly submitted himself to the logic of the machine.

This contrast is about identity. Gukesh plays from feeling. Ding plays from calculation, chasing not victory, but understanding.

The Cost of Beauty

Ding’s obsession with quality chess has made him a reluctant winner. After seeing a low-level blunder by his 2023 World Championship rival Ian Nepomniachtchi, Ding felt no joy. “I suddenly felt that this was not a high-quality game and my pursuit was not met.”

The fire to win evaporated. That scared him more than the loss.

To him, the most beautiful game he’s ever played wasn’t the one that crowned him champion. It was his 2017 victory against Bai Jinshi, a game he likened to a swordsman advancing with quiet precision, not brute force.

Even his famous 2019 win against Carlsen, in which he baited the Norwegian genius into overextending and then struck with a knight that had waited silently for eight moves, brought Ding only brief pride. “Everything happened in a split second,” he said, then deflected the glory.

Carlsen wasn’t used to morning games, he claimed. Maybe he was just more awake.

“Ding Chilling” and the Burden of Calm

To fans, Ding became “Ding Chilling” – the ice-calm genius who nibbled on almonds and ice cream while others cracked under pressure. But when a press conference host explained the meme to him, Ding responded flatly: “I haven’t eaten ice cream recently.”

It was unintentionally revealing. He doesn’t understand the performance of cool. He is not trying to look relaxed. He just is. Or at least, he hides anxiety behind stillness.

After winning the world title, his form declined. Poor health, fatigue, and self-doubt crept in. His parents asked him to skip events. He didn’t. He kept competing and kept falling. “It’s too difficult. It’s hard to endure. I was at the bottom a few times, so I changed my goal to avoid the bottom.”

A world champion afraid of last place. That’s Ding.

The Fragile Art of Risk

Modern chess is a minefield. With engines mapping the first 20 moves of every major opening and accuracy often exceeding 99%, mistakes are rarer, wins harder to come by. “If you want to win, you still have to take risky moves,” Ding said. But risk is dangerous. A single imprecision, and you’re done.

It’s a metaphor for life, he mused. People become more accurate, more polished, yet fate still turns on a leap into the unknown. Inaccuracy, he suggested, might also be a kind of accuracy, the human leaking out through the cracks.

In 2024, Ding lost his title to Gukesh in the final game. Four hours later, he was online playing Bughouse with friends, casually enjoying a variant that throws order to the wind. He wasn’t even feeling broken, just a relieve. A reminder that chess can still be fun.

But Ding is not the type to play for fun. At least, not anymore. “Playing chess requires grasping at the opponent’s minor mistakes and accumulating small wins into big ones,” he once said. That kind of grinding patience doesn’t leave much room for joy. He admits that he used to scorn players who fist-pumped after a win. “Winning is based on the failure of others. How can you ignore their feelings?”

The Philosopher Turned Artist

In the past two years, Ding has tried to transform, from engine to artist. From philosopher to improviser. “It is not easy to transform ‘philosophy’ into ‘art,’” he said. It’s like a magician trying to put a rabbit back into the hat, change the trick, and pull it out again. You already know the secret. How do you still surprise?

He is working on it. “My combat effectiveness has improved recently,” he said. “But my ability to improvise is still lacking.”

He admits he is afraid of losing. He once went unbeaten in 100 slow games because he clung so tightly to that fear. Even now, a loss wakes him up at night. And yet, when asked about his ambitions, Ding is humble to the point of indifference. “I want to focus on chess. There is no goal.”

In fact, his career itself seems shaped more by avoidance than ambition. He became a pro because school was too stressful. He became champion partly because Carlsen refused to defend the title. He didn’t chase the spotlight. It found him.

A Final Stalemate

Ding Liren is not the fiery genius of lore. He is no Fischer, no Botvinnik. He writes no notes to enemies, seeks no dominance. He is, instead, the quiet scholar in the corner of the library, reading positions like texts, analyzing variations like case law.

And yet, in trying to become as accurate as a machine, he’s only made his humanity more visible. His weariness. His melancholy. His reluctant pride. His strange joy at watching two engines do what he cannot.

He once said, “I don’t think about beating [the engine]. It’s impossible.” But maybe that’s not the point.

Maybe Ding Liren didn’t become world champion because he was the best at breaking the game. Maybe he became world champion because he tried so hard not to break it. Because he believed, deeply, that even in a game of machines, the beauty still matters.

And sometimes, when the knight jumps after eight silent moves, it still does.

I’m Xuan Binh, the founder of Attacking Chess, and the Deputy Head of Communications at the Vietnam Chess Federation (VCF). My chess.com and lichess rating is above 2300, in both blitz and bullet. Follow me on Twitter (X).