Valeri Beim’s 2011 book, Back to Basics: Strategy, is a serious and methodical attempt to classify positional advantages and explain how to turn them into wins.

As someone who has read a lot of chess literature, I found Beim’s teaching style refreshing, and his focus on fundamentals extremely valuable. The whole book is built around exploring “the essence of strategy, how it usually appears on the chessboard, and what it consists of.”

I. Teaching Style and Overall Structure

Right from the preface, Beim sets the tone with a clear message: “Playing chess is interesting – but playing and winning is even more interesting!” He draws a firm line between strategy and tactics. Strategy, he says, defines the quality of your position; tactics are the calculations you use to take advantage of that position. He even warns that being good at calculating “might be of no use in a bad position.”

One of his best demonstrations of this idea comes from comparing two games that use the same attacking motif: a typical kingside attack. He contrasts Pillsbury–Burn (Hastings 1895), where the tactic worked, with Yusupov–Illescas Cordoba (Ubeda 1997), where it failed. In the second game, the Spanish grandmaster “succumbed to the tempting opportunity to execute this old… trick,” but White defended calmly with 14.Kg3!. Beim argues that Pillsbury succeeded because “his positional strength before he began the combination was sufficient,” while Black in the Yusupov game should have “gradually improved the position of his army” instead of sacrificing too early. This idea—that good tactics come from good positions—is really the foundation of the entire book.

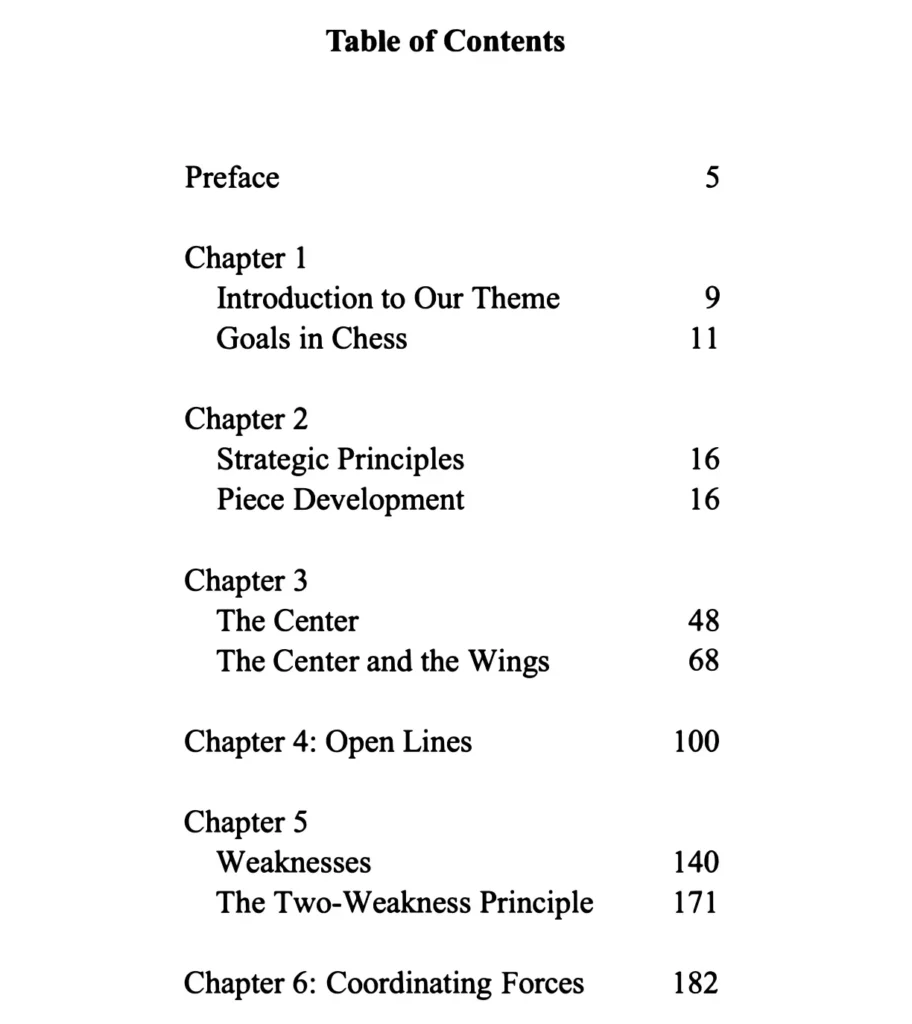

The book itself is very well organized. Beim sorts strategic themes into major chapters like Piece Development, The Center, Open Lines, Weaknesses, and Coordinating Forces. Even though he breaks them into categories, he reminds readers that these themes “are not likely to occur alone,” because in real games “everything here is connected closely.” His tone is confident and expert, and he draws most of his examples from strong players because, as he says, their decisions are based on “deep knowledge of the truths of chess play.”

II. Content Analysis: Strengths and Weaknesses

Strengths: Clear Explanations of Important Principles

1. Piece Development (Chapter 2)

Beim goes further than the usual advice about development. In the famous Anderssen–Kieseritzky game, he explains that even though Black moved pieces, they were “without connection… to the rest of the army.” He calls this a “complete lack of development.” Meanwhile, Anderssen developed properly, which allowed him to launch a brilliant and correctly calculated attack.

2. The Center (Chapter 3)

This chapter is one of the strongest in the book. Beim explains centralization with both logic and numbers: a knight on d4 can control up to eight times more squares than a knight on a1. That leads to one of his key messages: “Strive to centralize your pieces, especially your knights!” He also explains the idea of a forward outpost—an “invulnerable” central square supported by a pawn—and uses games like Smyslov–Rudakovsky (1945) to show how a centralized knight “can control the situation, no matter what course the game may take.”

3. Weaknesses (Chapter 5)

Beim defines a weakness in a practical way: it’s “anything that requires defending, over a sufficiently long period of time.” His explanation of how to fix a weakness is excellent. In the endgame Smyslov–Keres (1951), Keres slowly uses pawn moves like h5 and h4+ to “nail the h3-pawn in place,” forcing White’s king to stay passive. He calls this technique “fixing the weakness,” and the example makes it crystal clear.

4. Coordinating Forces (Chapter 6)

Beim says this principle is “superior, through its universality, compared to all the other principles.” Here he shows how concentrating pieces creates decisive power, often referred to as forming a “fist.” A great example is Capablanca–Tartakower (1924), where Capablanca’s king, rook, and advanced pawn come together to create “a high concentration of force in the decisive area of conflict.”

Weaknesses: Where the Book Falls Short

1. No Exercises, Despite the Difficulty

Even though Beim says beginners and experienced players can both learn from the material, he doesn’t include any exercises for readers to test themselves. This makes it harder for self-learners to engage with the ideas. Having positions to solve before seeing the analysis would make the book far more effective.

2. Sometimes Too Analytical

While deep analysis is useful, some sections feel overwhelming. In the Yusupov–Illescas game, for example, Beim avoids giving the full variation and writes: “I shall not overburden my readers’ attention with these analyses, just take my word for it!” He repeats this approach in the Morphy example, where he again asks readers to “take my word for it.” For a book aimed at people “taking their first steps,” this can feel a bit inaccessible.

3. Principles vs. Concrete Details

Beim often notes that chess principles “are constantly at war with one another.” While true, this sometimes leads to explanations that rely heavily on subtle positional details that newer players may find hard to judge. For example, in Lilienthal–Botvinnik, he shows that what looks like a strong centralized knight on e5 (supported by f4) is actually a mistake because it “was not in keeping with the character of the position!” The bigger lesson is that “it all depends on the concrete particulars of the position.” This is correct, but not always helpful for players who want clear, simple rules to follow.

III. Instructional Value and the Author’s Approach

Overall, the book is a fantastic instructional guide for players who know tactics but still struggle to convert good positions into wins.

For intermediate players (around 1500–2000 Elo), the book is especially valuable. The chapters on Weaknesses and Open Lines are great for learning how to build small positional advantages into something decisive. Beim gives strong examples, like Petrosian’s systematic control of the light squares in Petrosian–Hernandez (1979), or the “Second Front” strategy in Smyslov–Tal (1959).

Beim’s tone is precise and methodical. He starts the Introduction with a detailed explanation of key terms, using a daily-life analogy—a trip to the store—to show the difference between strategic planning (deciding goals or when to go) and tactical decisions (choosing the route or transfer points). This careful groundwork gives the book a high intellectual standard.

One of the most impressive moments is his analysis of Stolberg–Botvinnik (1940) in Chapter 3. The game shows the power of centralization and piece cooperation. Beim presents positions where White seems OK at first glance, then explains that the position is actually “very difficult, in a larger sense even lost for White” because of falling weaknesses and the “ideal cooperation of all the black pieces.” This ability to reveal deeper truths beneath the surface is one of the book’s biggest strengths.

IV. Conclusion and Recommendation

Back to Basics: Strategy by Valeri Beim is a deep, carefully researched look at positional play. It truly delivers on its promise to break down core strategic ideas that every serious chess player needs.

Its biggest strengths include:

- a clear structure

- strong explanations of how strategy and tactics interact

- excellent classical and modern examples

- deep, thoughtful analysis of important ideas like centralization, fixing weaknesses, and coordinating forces

Its weaknesses include:

- analysis that sometimes becomes too dense

- a lack of exercises for readers who want hands-on practice

Final Verdict

I strongly recommend this book to players rated around 1500 and above. If you often get good positions out of the opening but struggle to turn them into wins, this book gives you the strategic framework you need. Beim shows not just the principles of strategy, but the reasons behind them. Reading this book is like learning the grammar of positional chess: it may feel dry at times, but once you understand it, you can create full, well-constructed strategic “sentences” of your own.

Guest Author: Ethan Doyle

Grab Back to Basics: Strategy by Valeri Beim on Amazon here. Buying through this link supports this site at no extra cost to you.

AttackingChess Guest Contributors is a collective author profile representing chess enthusiasts, reviewers, coaches, and community members who contribute book reviews, insights, and educational material to the site.

Articles published under this profile may come from different writers with varying backgrounds in strategy, tournament experience, chess literature, and long-term training. All submissions are edited and fact-checked by the AttackingChess editorial team to ensure quality, accuracy, and practical value for readers.

This contributor profile is designed to give a voice to many chess lovers who want to share their perspectives without maintaining individual author accounts.